Rakia, 20 and her daughter, Nafissa, 3, Niger, 2005

Rakia lives in a miniscule straw hut. She is an orphan. Her mother died when she was young, her father died in an accident. She went to stay with her mother’s relatives where her uncle abused her. “I’ve been a sex worker since I was a child. A client got me pregnant. After I had my daughter, my relatives chased me from their home. We ended up here,” she says.

“There is nothing to eat here. I borrow food from neighbours. My daughter and I do not eat everyday, we did not eat yesterday and I have nothing to give my daughter tonight. I work from home. I put my daughter to sleep and then I go to work beside her. Men come to my home. I’ve never been a girl who goes on the street or to bars looking for clients. I can’t leave Nafissa home alone and I can’t take her with me. I sit outside my hut and the men come.”

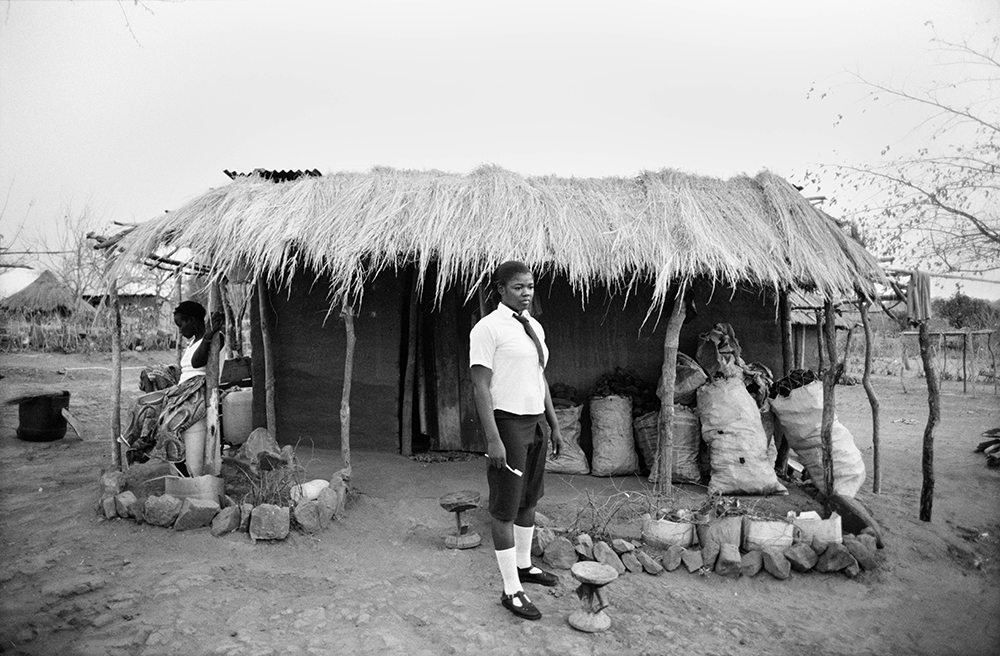

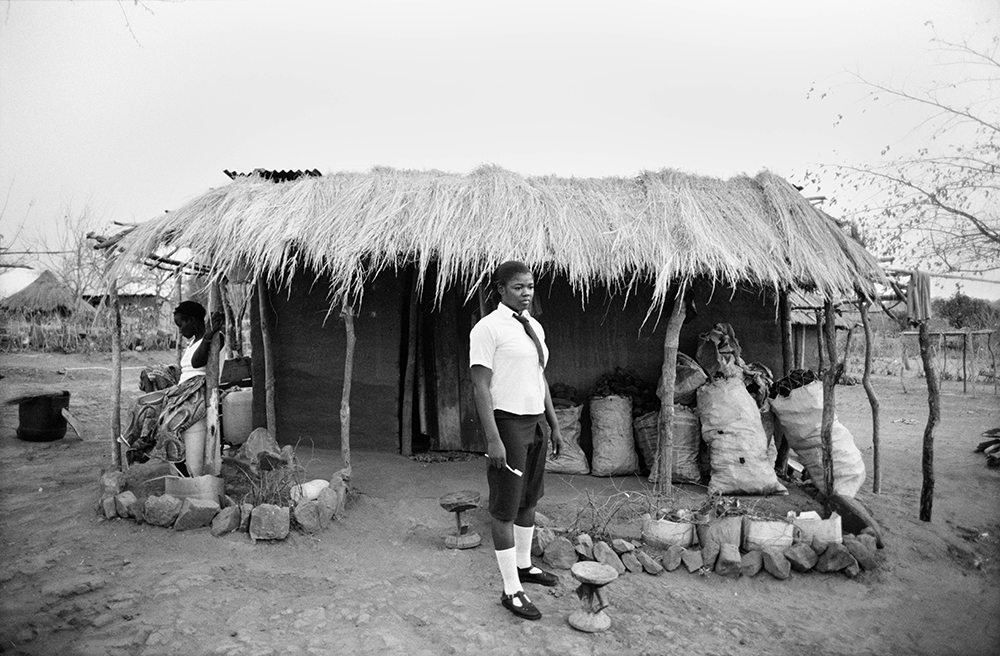

Malinda, 17, Niger, 2010

I was told Rakia was driven to mental instability by her circumstances and left the mining town where she had tried to support her child and herself. Like many young women she was driven from home, Rakia and Malinda [pictured here] and with no skills they were left to fend on their own. Malinda’s fellow ‘barmaids’ have become her family. It’s unlikely that her situation will change. Rakia has since resurfaced in another mining town where she continues to sell her body.

Queen Mother and Sex worker, Zambia, 2005

Girls are often expected to contribute to the family budget. Some are sent by their guardians to engage in sex work while other guardians turn a blind eye and receive food and other items the girl brings home. Young sex workers are often initiated into the sex trade by older girls or women. In this town a group of 16 year old girls said a quarter of their former classmates were in the trade due to the lack of alternative means of earning money. They are so poor that they go to a ‘Queen Mother’ to borrow clothes, and make up for the evening. On their return these girls have to pay about half their earnings to the Queen Mother. Although they are all aware of the dangers of HIV/AIDS most of the teenagers have never used a condom, often having sex with three or four men a night. Their clients insist on going Walayi or live wire – skin to skin. The women are not in a position to say no as competition is so great, their need to feed their families and themselves dependent on this income, and they are often threatened by the men. Many clients, often ‘Katondo boys’ (money changers), truck drivers, or corrupt policemen ,either don’t pay them or will only pay after they have ‘tasted’ (had sex first). The girl (on the right of the picture) later in the evening accepted a beer from a man in a bar and was told “You owe me,” as she was expected to have sex for the price of the beer she had already consumed (US$1, the sum normally charged by local sex workers). The young woman in the photograph has since died of AIDS.

Queen Mother, Zambia 2010

Life hasn’t changed for most young women here. For most young women, personal circumstances haven’t changed. A few have benefited from vocational training. However, the Queen Mother’s modest shack, has become a two-bedroom house which is part her own motel and bar. Business is booming and she is building a business empire: she not only also owns the town’s other most successful bar, but has several cars and during my stay purchased a small truck. Her former ‘girls’ would like a job, but the Queen Mother needs either young women with skills such as accounting, or young attractive ones who will encourage her patrons to buy more beer. She no longer runs her original business as she no longer has the time to hand out dresses or to apply make-up.

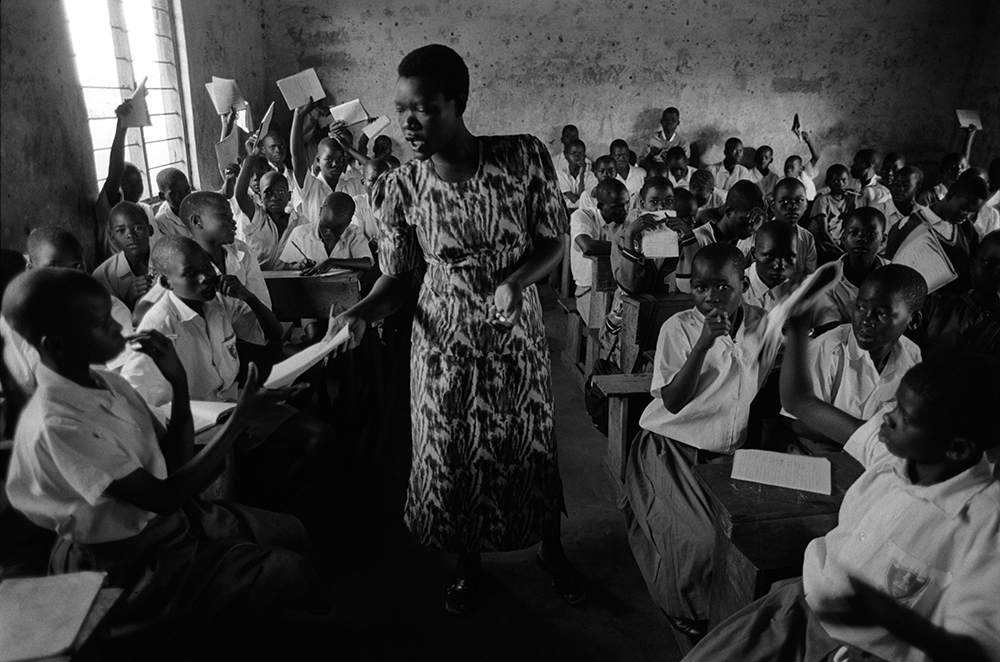

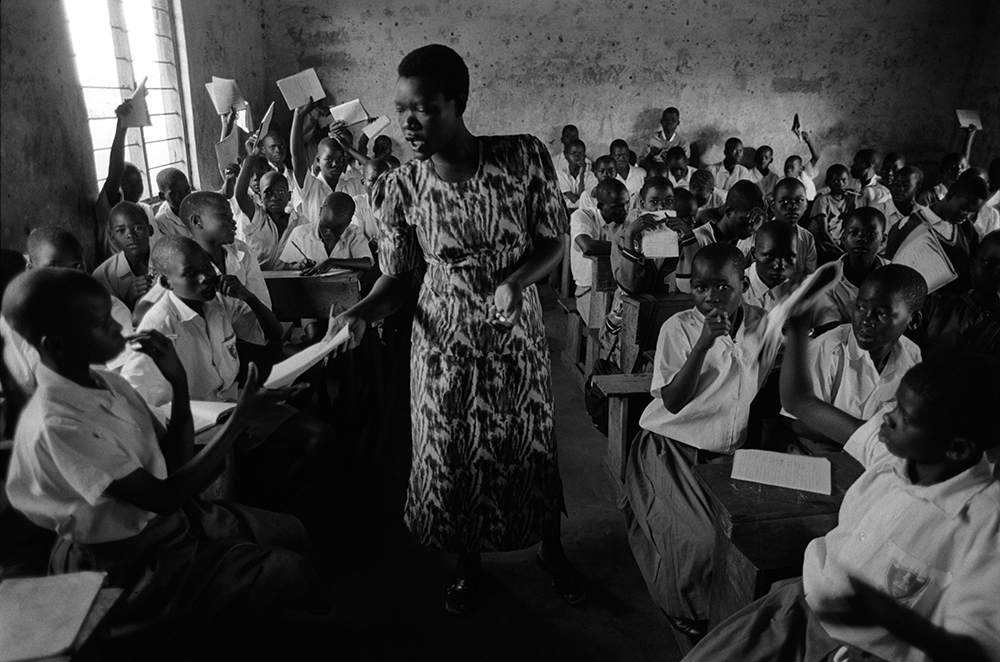

School, Northern Uganda, 2005

Most of the children in this school will complete a full course of primary education in class of a 122 children. The school has great difficulty recruiting teachers because their budget is so tight that chalk is rationed and a lot of trained teachers have died of malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. There are a total of 1500 children in this school of which 900 are orphans (having either lost one or both parents). Up to Grade 7 is free, but children must have uniforms and when you don’t come to school in one (some children are too poor to have a complete uniform), you get punished and are made to clean the classrooms, yard and toilets. For 2000 Shillings (US$1.10) per semester children can receive school meals. However for some, even this is beyond their means and they will either go without or make up to a 40-minute roundtrip home for a bowl of gruel at lunchtime.

School, Northern Uganda, 2011

Overcrowded classrooms remain the norm. I counted 135 children in this classroom. Everything is in short supply, not only toilets, but desks, pens, pencils and exercise books, and chalk for the blackboards. The local education authority complains that, national and international objectives favour goals that have resulted in “quantity over quality”.

Brothers Ratana 14, Sopeak 11, Sopoas 10, Cambodia, 2005

Children, adolescents, elderly men and pregnant women can be found trudging through the slush of this refuse dump. 24-hours a day, whether in scorching heat or tropical downpour they wait for the next dumpster to tip its refuse on to the mountain. At night they will hire battery-powered headlamps and work until dawn when others, unable to afford a headlamp, take over. The recyclers will often scoop up and eat someone else’s discarded rice, or gnaw at watermelon rinds that have been all but been picked clean. To cope with the stench, the hard work, tiredness and hunger, many children depend on drugs. One of the chemicals used here, the Ma, are amphetamines made in Burma. Children say that when they take it, it anaesthetises their tiredness - they also don’t feel as hungry, they can work longer hours and endure more hardship. Many children combine school with recycling; few are able to study properly as they devote their day to school and the evening to earning a living to help support their families and the ‘unofficial school fees’ charged by teachers. San Sok Heng’s, the brother’s [pictured] mother, has had twelve pregnancies, “I had two miscarriages and two abortions. I have eight children that are living. “We have great difficulty feeding our children. None of the children are in school. Going to school here costs 500 riel per day. It’s not an official fee but the teachers will take money from the children. It’s too costly to send them to the government’s school. We have applied to the local Non-government school run by a charity but there is not enough space for our children. Now with the night working at the dump, even if the children went to school they wouldn’t be able to concentrate. They work from four o’clock in the evening until six or seven in the morning. They return home to sleep and eat lunch and then leave home again at four o’clock.”

Recycling, Cambodia 2010

Children, adolescents, elderly men and pregnant women continue to trudge through the slush of a refuse dump – the new site, on the outskirts of the capital is privately owned and they have hired the police, and a private security firm to enforce permits to scavenge, but many work clandestinely. Two of the original boys I photographed have taken opposite paths. One has a wife and child but still works as a scavenger and remains a substance abuser, now to smoking opium. The other has been in and out of school, but has a dream to be a supervisor in the food and beverage business.

Bridget, 16, Zambia 2005

Bridget no longer goes to secondary school – however two of her brothers continue to go. She was desperate to remain at school, “I went into sex work to try and remain in school,” she says. “When I saw that my father stopped making a contribution and my mother couldn’t afford my books, uniform or fees, I decided to do something about it personally. I first slept with a man to buy exercise books and then began to frequent truck stops to sell sex to truckers. The regular price is $US1 per session. I’ve stopped going to school now and am engaged in sex work completely, as I couldn’t keep doing both at the same time. None of my customers have ever used a condom. I have been lucky so far – I haven’t fallen pregnant or haven’t terminated any pregnancy.”

Bridget, 21, Zambia 2010

When I first reach Bridget’s hut, she is resting, but she gets up and apologies, “I’m feeling ill,” she thin if not gaunt, doesn’t look well and is visibly frail patting her eyes with a handkerchief – she has a problem with her vision. “I didn’t think I would ever see you again. In another 5 years time I will be dead.” Since my last visit Bridget lost her first baby with diarrhoea, and gave birth to a second baby. She tells me she was hospitalised in 2007 and was in and out of consciousness. Bridget is now HIV+ and although her ARV treatment is free she hasn’t the money to pay for the food needed to be able to take the medication and be effective. Bridget was not surprised when she was told she was HIV+, “None of my clients used a condom – I just wanted to support my family. I nearly realised my goal of returning to school, but my daughter got sick and all the money I had saved went to pay for the medical expenses and her funeral”.

Channa, 12 and her brother Pau age 9, Cambodia, 2005

Channa currently supports her mother and brother. Channa and Pau live in a 2m50 by 2metre hut that is too low to stand up straight, in a squatter’s neighbourhood with their mother who is too ill to work. Channa goes to school in the morning and then goes to earn money in the afternoon and evening. Pau shines shoes, Channa has a weighing scale which she charges 100 riel (2.5 US cents) per client to be weighed. The previous day police chased Channa and Pau, Channa dropped her scales and the glass over the measuring dial broke. Channa explains, “Shortly before my [blind] grandmother died, she was given US$20 by a passer-by, she told my Mother to buy something that was an investment to earn revenue”. For dinner, they usually eat whatever they can find on the street.

Channa, 12, Cambodia 2010

Channa and her family were forcibly evicted from their dwelling in the capital. “They told us a truck would show up to take us to our new square of land. They promised us a property title to our ‘bungalow’ – we were driven 45 minutes from town there was nothing, they dropped all our belongings on to a field. The first night we made a tent out of the plastic we had”. Channa left home and is now married to a truck driver, but Rihorn, her mother, is not sure what she does for a living – Channa is at a vulnerable age when many young, poor women become ‘hostesses’ or sex workers. Channa was always first or second in her class, considered an exceptional student until she was forced to drop out of school to help her sick mother.

Irene, 17, Zambia 2005

“I am the fourth born of five children and my father divorced my mother when I was about four years old. He has since remarried. I went up to Grade Seven but I could not go very far because my mother had no money. I started sex work at the age of thirteen, because I so wanted to continue at school, I used the money through sex work to buy books and pens and sometimes clothes. Later on I also bought some lotion. My mother did not ask me how I bought these because she never provided what I needed. She may have suspected what I was doing but did not dare to ask. My Mother burns charcoal and sells it, it’s just enough to buy food and soap. Besides this, mum is sick and she does not make as much as she used to. She feels dizzy, faints from time to time and feels weak. She hasn’t seen a doctor about her sickness, because we do not have enough money for hospital bills or even for a traditional healer, besides my mother would rather buy food for us and pray that God heals her.” Money is often so short that Irene gets food on credit from the market and when she can’t repay her debt she must do so in kind by having sex with her creditor (stallkeeper) often for the equivalent of three bowls of peanuts. “If I could be born again,” says Irene, “I would want to be born as a man.”

Chimunya 20, Irene’s Sister, Zambia 2010

Chimunya is only a year younger than Irene, she has witnessed most of the trials and tribulations that her family have faced. Whilst her mother spent what little money the family earned on her sons education, Chimunya did the housework and read English books. Now thanks to Lois, her eldest sister, and her parents who have managed to make some savings, she has returned to school and is not embarrassed to sit in a classroom with children who are upto 7 years younger than she is. Chimunya wants to be a nurse.

Aida 13 and Tatevik two and a half, Armenia, 2005

Aida is often ‘mother’ to her two-and-a-half year old sister Tatevik as her mother and 14-year-old brother seek seasonal work in the countryside. Aida gets up at 8am and dresses her sister. At 9am they have a cup of tea with a small piece of the cheapest bread. Then Aida begins doing her housework, draws water from a communal tap in to plastic bottles to warm the water under the sun and to do the washing-up. There is no electricity or running water in their house. Aida then washes their clothes and later plays with her younger sister she dotes on. At 3pm they have a small plate of soup and have nothing more till 9 in the evening, when they have a cup of tea, but this time without bread. Aida is worried about her sister’s health, “I had two sister’s who died of pneumonia [one at 2 months the other at 2 years old] and the doctor says that unless Tatevik receives good shelter and adequate food she will also die of pneumonia.

Tatevik, 8, Armenia 2010

Since my visit in 2005, Tatevik contracted tuberculosis. I found her in a sanatorium 5 hours drive from her home. She doesn’t want to return home, but she misses Aida, her sister who she hasn’t seen for 2 years. Aida has since married so as not to be a burden to her mother. She is now pregnant with her second child living in the same conditions - no running water, electricity and heating that she left behind. She fears for the health of her children as she cannot afford to feed them properly and has no money for medication when her daughter is ill.

Gloria 13, Judith 11, Miriam 5 and Monica 32 months, Uganda 2005

When their father died of AIDS, Gloria, Judith, Miriam, Monica and their mother were chased from their home by his brother. They rented a hut but four months ago their mother also died of AIDS. Monica, the youngest of the four sisters, is very weak, suffers form malaria and does not eat much of what little food they can scratch together – rarely more than a bowl of gruel a day for the fours sisters, divided between breakfast and lunch and almost never anything for dinner. Although Monica is 2 years and 8 months old, she is only as tall as their neighbour’s one year old. The neighbour fears that because Monica’s mother, who was afraid to be tested for HIV, breastfed her as she was dying from AIDS, Monica might have contracted the virus.

Gloria 18, Miriam 10, and Monica 7, Uganda 2010

Peniless, in rent arrears facing eviction from their hut, they were the first orphans to be accepted in to an orphanage set up by born again Christians. Subsequently Judith left in circumstances that are far from clear. Living in vulnerable circumstances, she was abused at the hands of a young man who had been a fellow classmate. In June she gave birth to a healthy child and mother and daughter have been taken fostered by a couple.

Husseina (tied to a cushion) and Hussaina (in her aunt’s lap), both 40 days old, Niger 2005

When Husseina and Hussaina’s mother went into labour the family had to take out a loan to pay for the ambulance to take her to the nearest hospital 72 kilometres away. It was only after 18-year-old Aisha gave birth to her first baby that they were caught unawares – there was a twin (the nearest ultrasound is 200 kilometres away in the capital). Aisha had a caesarean section but died as they removed the second baby. Today, the twins are being cared for by their Aunt Fatima. Their father is looking for work abroad and doesn’t know he has twins. However, Fatima worries for the twins’ survival. Already in debt due to the drought and the ambulance fees, she has neither the money to pay for their vaccinations nor the money to buy the required quantity of milk powder. “Even my goat doesn’t produce enough milk,” she says, “all that is left for me is to ask God to feed and clothe them.”

Husseina and Hussaina’s grandmother, Niger 2010

Aunt Fatima had reason to worry about the twin’s survival: 6 months after I visited, Husseina and Hussaina died within 3 days of each other. Their Aunt having been unable to afford to buy milk formula (US$5 per week per child).

There is no doctor is this town, the ‘Major’ or head nurse told me, “A lot of deaths could be prevented with dissemination programmes for expectant mothers. However look at the CSI (clinic) this morning – we’re overrun. We don’t have the personnel to run an information campaign for pregnant mothers.” One positive change in the last 5 years: ambulances are free and this alone might have saved Husseina and Hussaina’s mother’s life.

Abbas, 15, Niger 2005

Abbas has worked in the mines for three years. He works from six am until seven pm, seven days a week, 363 days a year – sometimes Abbas goes back in the evening to do a further two to four hours work. He has never been to school and can’t read or write. Although his village is 12 kilometres from the mine he hasn’t been home since he arrived at the mine and has only seen his father once. About a year ago, his boss fell down the 22-metre hole and died. “I’m not sure how old he was. I was afraid to go down the hole after that happened. But I have to earn money. So I go down.” There are no safety measures in the mine, no ropes or guidelines down to the subterranean galleries where there are no lights, joists or beams. He is meant to send money home, but has never earned enough to do so. “Misery brought me here,” says Abbas. He knows that the gold he is trying to mine is precious but he has never seen a product made of gold.

Abbas, 20, Niger 2010

Abbas no longer works down the mineshaft but washing the slag to extract gold dust. Whereas, he was unable to send money home when working at the rockface, he now has enough money to buy bread and soap for his mother and 13 year old wife. Although a school was founded in Abbas’s village in 2005 the school’s teacher is battling both tradition and poverty in order to get children to go to class. As Abbas explained to me he does not wish his wife to go to school because, “I want a girl who is not wise and doesn’t know the ways of the world so that I can control her and so she will not be influenced by what I have seen [the mining village] neither he or his wife have been to school.

Border Town, Zambia 2005

Without skills or even with limited skills jobs are hard to come. Many people without work are attracted to border towns which are often busy trading posts with a large turnover of money and visitors who have been away from home and are looking for company. This often leads to a thriving market in sex workers. Here many women who have been unable to find work elsewhere are able to sell their bodies and companionship to the hundreds of truck drivers who pass through this border town every week. Trade is brisk 24-hours a day. Drivers often press the truck’s horn and shout “Coffin!” or “Bitch!” at the girls and women looking for business. Some girls and women become ‘Take Aways’ a term used for those that take up the offer to become the truck drivers travelling companion. However, they are often dumped half way across the country or sometimes in another country with no means of getting home other than by offering sex.

Border Town, Zambia 2010

Little has changed for most women living in this border town – a victim support unit has been set up – but gender equality remains a distant dream, boys are still favoured when it comes to getting an education, leaving many young woman without any skills. A few have received vocational training thanks to non-governmental organisations, but that funding has dried up since the global economic downturn. To make matters worse, local sex workers now compete with refugees who work for half local prices. Here, nothing is free: giving birth is meant to be free, but you get charged for your bed, the baby blanket, the bathing dish, etc… A local person refered to government employees as, “a cartel of wrongdoers.”

Jeeva, India 2005

Jeeva is a transsexual having undergone a surgical operation to his body. She is angry that others like her who have become transsexuals aren’t recognised by the authorities – they are denied identity papers and passports. She and others like her have given themselves self-published identity papers that state they are ‘third gender’. Like Jeeva many come from villages (his parents were not happy with his identity) and migrate to the cities where they live with other transsexuals in slum dwellings. Denied papers, Jeeva explains, “We are forced to either beg or take up sex work. We have no alternative as no one will give us a job.” Casual sex work puts them in danger of contracting HIV/AIDS and transmitting the virus to multiple partners. According to Jeeva in the northern part of her city there are some 2000 third gender sex workers, most of whom have unprotected sex and have never been tested for HIV/AIDS – no one would ever admit to being HIV positive. Jeeva has only recently become aware of HIV/AIDS. She is better off than a casual labourer with a well-furnished apartment where a gang of teenagers are constantly present and who are close to him physically.

Jeeva, India 2010

Jeeva’s dreams are being realised, the state, one of the few in India has recognised transgender people, granting them ID papers as a result. This has opened many doors to mainstream life for them including starting businesses, qualifying for loans, access to tertiary education, … Jeeva explains that changes have also resulted in removing many obstacles to having stable partners, therefore reducing sexually risky behaviour and the spread of HIV/AIDS. Jeeva now not only runs a transgender website, but has gained a BA in sociology and wants to get a degree in law.

Ayaz, 10, India 2005

Last year, Ayaz’s father developed a fever and a chronic cough. He was admitted to a TB hospital where he developed mouth ulcers so severe he could not eat. He grew very weak and died after a few days. At the time, Ayaz’s mother didn’t know he had died of Aids – she didn’t even know about the illness. Now, both she and Ayaz’s six-year-old brother have tested HIV positive but Ayaz and his two-year old sister are negative.

Ayaz is no longer in school as he needs to support his family. He works sorting second-hand clothes for his uncle’s business, a 10-hour shift for 10 rupees (US$0.22) a day. Ayaz’s mother is currently searching for work, and wants him to study, but she cannot live without his income. Ayaz’s mother still finds it difficult to accept her status, “Being a woman of faith, I wondered, ‘why me?’ she says. “I was very angry with my husband as my younger son was also infected. I want to provide my children with a good life for as long as I can.”

Ayaz, 15, India 2010

Thanks to a neighbour and teacher who not only tutored Ayaz but help support the family, they have overcome the worst of their hardships. Ayaz, like his younger brother, have been sent to orphanages, however, Ayaz was back home during my visit to look after his younger sister and mother as she had 15 days in hospital to observe how she took to the ART (antiretroviral treatment). Although Ayaz had dropped out of school to earn a living at 8 and didn’t return until he was 12, he is now one of the top students in his year and one of the top 3 in mathematics. Ayaz misses his family, and without his support, his mother finds life very difficult, surviving on menial jobs: cleaning a railway station and an office, but is often overcome by tiredness due to her antiretroviral treatment.

Selvi, 30, India 2005

Selvi contracted HIV/AIDS from her husband and she is now terminally ill. She has two children; an eight-year-old boy and a six-year-old girl. In early 2004, Selvi gave birth to a male baby, who died of malnutrition when just four months old. Her husband is a daily wage labourer and her son runs errands for a teashop. Without any means for livelihood, Selvi has now rented out her shanty house, a lean-to on the pavement (in the picture) for 150 Rupees (US$3.40) per month and they now sleep in the open, but they are allowed ‘home’ to cook and to store their belongings. Her husband is not taking care of her now. He is not bothered about her deteriorating health. She doesn’t receive any monetary support from him. Since this photograph was taken Selvi has developed a tumour in her neck and has been admitted to a hospital 30 kms away. Her husband didn’t take her to the hospital she went there alone. She worries constantly, “What will happen to my children when I die?”

Kousalya, Selvi’s 11 year old daughter, India 2010

Kousalya knew her mother was seriously ill, she flagged down several rickshaw drivers to take her mother to hospital, but unable to pay, they refused. Selvi died several hours later in the early hours of the morning next to her two children. Selvi’s husband Mohan returned to look after his children, but as he explained, “For how long? I receive ART (antiretroviral treatment) but I can’t take it as I don’t have enough money to eat regularly. I have to decide whether to feed my children or myself to prolong my life to help them.” Unknown to Mohan, he repeats the same words his wife said to me 5 years previously, “What will happen to my children when I die?”

Chariya, 21, Cambodia 2005

Chariya is expecting her first child she is seven months pregnant. “My stomach has been hurting for several months now and I do not have money to go to the hospital [2,000 riel US$0.50). Just to have the midwife come to my house would cost around 5,000 riel ($1.25) to 6,000 riel. Whenever I get a stomach pain I sleep on this wooden bench outside of my house [she lives with her husband at her aunt’s home] and hold my stomach until the pain goes away. I don’t know what to do to make the pain stop. Once my aunt bought a bag of intravenous serum for me. The local pharmacy man - we call him doctor - helps to hook it up to my hand. Right now I am very worried about the delivery because I don’t know where to go and what to do. I used to sell sweets and dumplings to help my aunt take care of us. Now that I am so ill, I cannot help her. She sells eggs along the riverside, but the rainy season is not too good for business. My husband Ly Den tries to help too but is unemployed.

Chariya and family, Cambodia 2010

Chariya was taken by a non-governmental organisation to a clinic where she was told she might have lost her child and died had she not been brought to the clinic. As a result of her visit and regular check-ups she gave birth to a child that she named after the charity. Chariya and her family, like thousands of other families living in the centre of the capital were evicted from their homes. “There was a lot of violence as the bulldozers moved in, no one was killed, but there were a lot of injuries. We were given help by an NGO to build this shack, but we have built where there will be a street, so we will be forced to move again – everytime we are promised, ‘next time’, but everytime ‘next time’ comes, they make the promise again. My health is suffering, you can see how thin I am, the second baby doesn’t get any breast milk, because I don’t have any to give. Sometimes we have to borrow money for food and medicine, but some people won’t lend us money because we already owe money. I am four months pregnant, it wasn’t planned, I was taking the pill, but it still happened.”

Francisca, 50, Honduras 2005

Francisca is a widow. After 31 years of marriage to Victor Manuel he committed suicide, as he couldn’t bear to live any longer with his alcoholism. Francisca, has 10 children, most live at home as do two son-in-laws and two grandchildren. In all 12 members of her extended family live under the same roof sharing their small and overcrowded dwelling. Francisca is the first to rise at 5am, all of them take it in turns to wash and brush their teeth by drawing water from an oil drum that is their reservoir. The daughters will set to work washing clothes on a slab of concrete and then iron the dried laundry using the seats of their armchair as an ironing board. The boys will polish their own shoes. During the rainy season water will often course through their house and leave them under several inches of water.

Francisca’s daughters, Honduras, 2011

Like many of the cities barrios, this neighbourhood remains overcrowded and noisy with little or no personal space, but this neighbourhood is now connected to the electric grid which has changed many of the barrio dwellers lives. As fast as rains wash away homes, the hillside is bolstered against the next landslide. Tempers fray quickly, gangs and family violence are never far away, women suffer the brunt of the abuses that occur. More often than not, it’s the women who have to leave home and find a new dwelling, more often than not, taking a downgrade in living standards, moving to the hills further and further from the city centre. The increasing incidents of domestic violence are not reported for fear of reprisals.

Imbaki, Niger 2005

These Tuareg used to own a hundred head of cattle; goats, cows, camels and donkeys per family. Armed bandits have stolen their camels; the drought has claimed all but 2 or 3 cows or goats. All the young men except for the ironsmith have left on ‘Exode’ to neighbouring countries to find work as the last harvest failed and there is no money to buy grain from the market or to purchase seed for planting the next season’s crop. For the majority of those left there are days when there is nothing to eat, the mothers have no milk for breastfeeding their babies. Some scratched the dry riverbed looking for tubers, their sole nourishment but now the rains have started it is impossible to find them beneath the water’s surface. Their remaining animals are dying for lack of straw. Here, there is no infrastructure: no roads, no electricity, no telephone, no school, no clinic, no health worker, no seeds, no fertiliser, no irrigation system. Hunger, disease and poverty are endemic.

Imbaki, Niger 2010

Five years after my first visit, hunger, disease and poverty remain endemic. An emergency feeding centre remains in place. Many children continue to die, unlike five years previously few from severe malnutrition and starvation but mainly from malaria. Drugs are not available, when they are, some clinics are supplied with drugs form international agencies that are either beyond their expiration date, or drugs that are now resistant and ineffective to the local malaria parasite. Malaria kills over two and a half million people annually, mainly in Africa, sub-standard or ineffective drugs could account for over 200,000 of those deaths.

Orphanage for HIV positive children, India 2005

8 children from the ages of three to twelve live together with their teacher in the last house in a street at the end of the neighbourhood. No other orphanage would accept these orphaned children because they are HIV positive. Even the neighbours complain about their presence. Their teacher and her daughter are also HIV positive so they live with the other children because they too were chased from their family, first from her in-laws then her own family refused to allow them home. She explains, “Everyone stays away from us; our families, our neighbours. I hope that society will change so that my daughter can see her father. I am sure it will take time, maybe 10 years. I know where my husband is, but I think my mother-in-law told him I am dead.” She has difficulty answering the children’s questions, “They go out, eat, study, but they know something is wrong. ‘Why are we here?’ they asked, ‘Why are we outcasts?’ ‘Why can’t we go to school like other children?’” When the deputy director was asked how long the children will live in this house, he answered, “Until they die.”

Orphanage for HIV positive children, India 2010

The orphanage has been forced to move several times since 2005 as neighbours have gone to great lengths, writing to the police, local and state government to have them evicted. However, the director of the orphanage has found a school that has agreed for the children to attend classes. The orphanage has also grown from 8 to 13 children but once they’re back from school, they keep to themselves, playing indoor games rather than outdoor games because of the local hostility to them. Their original teacher, who was HIV+ and living at the orphanage, family have had a change of heart and she is now living with her mother and sister, however, she wouldn’t dare to admit that she was HIV+ at her new job for fear of being immediately dismissed.

Mining town, Niger 2005

This town can only be reached after a long journey across a desert track. , There are 6,000 miners out of this town’s population of 20,000. They come from villages across Niger as well as neighbouring countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Togo, Ghana) to work here. They are mining for gold and most are unaware of its subsequent use or value. “Some men work here for three months and earn nothing. One day you might get lucky but there are no guarantees,” says Abdoulaye Soumana, manager of World Vision’s AIDS education project. Temperatures can reach 45C+. There are few trees on the bald hilltops that are heaped with mounds of earth extracted from the mines.

Niger 2010

In the last 5 years schools have been established in villages where none existed. Only a fraction of school age children attend classes; a majority of boys as both tradition and poverty hold parents back from sending their children, particularly their daughters to school.

Whilst some parents have contributed books and built their own schools – the government has paid for the bricks, other parents cannot afford to send their children to school because if the children don’t earn money there will not be enough food to feed the family.

Channa 12, Cambodia 2005

Channa currently supports her mother and brother. Channa lives in a two-by-two-metre hut that is too low to stand up straight, in a squatter’s neighbourhood, with their mother who is too ill to work. Channa goes to school in the morning and then goes to earn money in the afternoon and evening. Channa has a weighing scale which she charges 100 riel [2.5 US cents] per client to be weighed. The previous day police chased Channa and her brother Pau; Channa dropped her scales and the glass over the measuring dial broke. Channa explains: ‘Shortly before my (blind) grandmother died, she was given US$ 20 by a passer-by, she told my mother to buy something that was an investment to earn revenue’. For dinner, they usually eat whatever they can find on the street.

Pau, 14, Cambodia 2010

I had great difficulty tracing Pau. He was eventually traced to a juvenile prison where he had been languishing for over two months, he was never charged, or brought to trial. It was only by enlisting the help of a human rights lawyer that he was released. Rihorn, his mother, has subsisted from the meagre earnings her son brought home. In his absence she had to borrow money from a ‘friendly lady’ paying loan shark rates of 7.5% per month, creating an even greater burden for Pau who has returned to shoe shining, the only job he has known since I first met him when he was 9 years old. Pau would liked to have continued at school, but even prior to his arrest, they were in too much debt for him not to earn a living.

Estancia Arca, Bolivia, 2005

There are 25 families in this community - that’s approximately 400 people. Last year 6 mothers and children died here during childbirth. The nearest medical help is a hospital three hours away by bicycle. Then it will take another hour for the ambulance to reach the community and a further hour to take the patient back to the hospital. In other words any mother or child requiring urgent medical attention will have to wait a minimum of 5 hours before receiving treatment.

Estancia Arca, Bolivia, 2010

Since 2005 only 2 women and children have died during childbirth - a direct result of women from Estancia having access to a pre-natal clinic and a medical auxiliary who visits once a month, although I was told ‘this sometimes doesn’t happen’. The community’s first one-classroom, one-teacher school was recently opened: built by a non-governmental organisation with the government providing the teachers.

Eugenia 10, Bolivia 2005

Eugenia spends her days shepherding her family’s llamas and sheep. None of the four girls in the family go to school (there are only 30 children in this community and out of those only 10 go to school; 7 are boys and 3 girls). Her brother who does go to school has to walk three hours to get to school, he sets off before sunrise at about 6:30am and leaves school at 3:30 in the afternoon to get back just before nightfall. So in addition to parents requiring their children especially their daughters to do regular work, the community leaders say that the nearest school is too far and too dangerous for the girls who would only reach home late in the evening, what’s more, “School materials are too expensive.”

Eugenia 15, Bolivia 2010 (left in picture)

Eugenia, her father, and six brothers and sisters have migrated to the nearest city, joining tens of thousands of people who have made the same move in search of jobs and a decent living. Anselmo, Eugenia’s father, sold enough of his llamas to purchase a plot of land and to build a single room where Eugenia’s six brothers and sisters share two beds. Eugenia now attends school as do three of her siblings. Anselmo is determined that they remain in school to learn Spanish so they don’t suffer discrimination and have a future. Anselmo now works as a porter in the city leaving Martha, his wife, at home to take care of their llamas.

Rakia, 20 and her daughter, Nafissa, 3, Niger, 2005

Rakia lives in a miniscule straw hut. She is an orphan. Her mother died when she was young, her father died in an accident. She went to stay with her mother’s relatives where her uncle abused her. “I’ve been a sex worker since I was a child. A client got me pregnant. After I had my daughter, my relatives chased me from their home. We ended up here,” she says.

“There is nothing to eat here. I borrow food from neighbours. My daughter and I do not eat everyday, we did not eat yesterday and I have nothing to give my daughter tonight. I work from home. I put my daughter to sleep and then I go to work beside her. Men come to my home. I’ve never been a girl who goes on the street or to bars looking for clients. I can’t leave Nafissa home alone and I can’t take her with me. I sit outside my hut and the men come.”

Imbaki, Niger 2005

These Tuareg used to own a hundred head of cattle; goats, cows, camels and donkeys per family. Armed bandits have stolen their camels; the drought has claimed all but 2 or 3 cows or goats. All the young men except for the ironsmith have left on ‘Exode’ to neighbouring countries to find work as the last harvest failed and there is no money to buy grain from the market or to purchase seed for planting the next season’s crop. For the majority of those left there are days when there is nothing to eat, the mothers have no milk for breastfeeding their babies. Some scratched the dry riverbed looking for tubers, their sole nourishment but now the rains have started it is impossible to find them beneath the water’s surface. Their remaining animals are dying for lack of straw. Here, there is no infrastructure: no roads, no electricity, no telephone, no school, no clinic, no health worker, no seeds, no fertiliser, no irrigation system. Hunger, disease and poverty are endemic.

Malinda, 17, Niger, 2010

I was told Rakia was driven to mental instability by her circumstances and left the mining town where she had tried to support her child and herself. Like many young women she was driven from home, Rakia and Malinda [pictured here] and with no skills they were left to fend on their own. Malinda’s fellow ‘barmaids’ have become her family. It’s unlikely that her situation will change. Rakia has since resurfaced in another mining town where she continues to sell her body.

REVISITED

Changes 2005 - 2010

2005

All the pictures from 2005

2010

All the pictures from 2010